[A peek behind the sausage factory curtain of blog ops: There was a brief moment on Friday night when I could have written this post but decided to go to sleep instead. 36 hours later, I am frenetically making up on lost time from the courtyard of a hostel in the Bellavista neighborhood of Santiago. The hostel has Wifi but doesn’t allow me to connect to Slack, so I can’t post photos of most things I’m writing about. Sorry.]

After our final dinner on the mountain, were joined by the resident electrical engineer to consult about finding a resistor for the cam LLOWFS shutter that we installed earlier this week. “I know it’s Friday evening”, Jared said, “but is it possible to do this tonight?” “Every day is the same here,” Pato replied. “Except for Sundays, when there are empanadas.”

Ninety minutes later we had a working shutter and a satisfied PI. “That’s a nice small victory at the end of the trip.” There were several frustrations, setbacks and difficulties with this engineering run. Good progress was made however across the board, and I think that all of us left the mountain feeling satisfied about the time spent through the process.

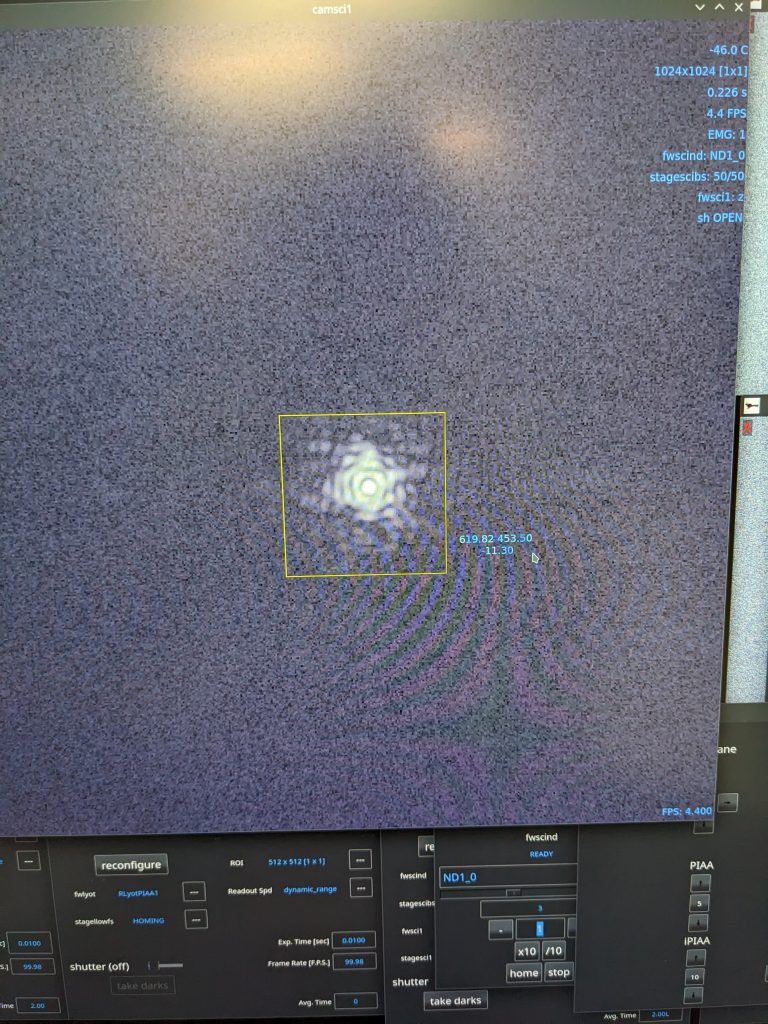

The main reason why I went to LCO this October was to overhaul the PIAA (phase induced amplitude apodization) system so that it could be used without needing alignment on-sky. The system consists of four lenses which need to be immaculately aligned with respect to each other. Relative translations of as little as 10um between lenses cause dramatic PSF degradation, meaning that previous runs required opening up the system after coupling to the telescope, and gingerly turning hand-knobs while squinting at a lagging video feed of starlight. No combination of the Thorlabs or Newport catalogues carried actuated lens assemblies that could provide this level of two-axis remote alignment, so we decided to machine picomotor interfaces into the existing cage plates that we’d been using to hold our optics. Getting the rough optomechanics to work with the old design did have some difficulties, and scientists that enjoy playing “find the shim” will see one in an unexpected place. After the system was installed and controllable with a slick new GUI, however, the stressful alignment process that used to take half a day could repeatedly dialed in within 30 minutes. It was, as Maggie said yesterday, a deeply therapeutic experience.

After finishing my work and taking some lab-data testing the extinction of the laser source, we were ready to start buttoning up the system and getting the lab ready for the observing run in some four weeks time. While Jared and Jay developed the checklist required for the first sans-PI run in MagAO-X history, I spent a thoroughly enjoyable hour cleaning the lab and organizing the piecemeal Allen key sets that had been OCD annoyances over the past week. Although I was not successful in the dream of “every key for every set”, and although our box of misfit keys continues to grow, I hope that the next run will be able to kick off with a fresh, organized start. A big part of the run turned out to be giving MagAO-X the TLC that can be often delayed by urgent actions or on-sky timelines. Maggie did excellent work in re-routing cables to clean up chaotic areas and provide a modicum of organization to an optical bench that can otherwise appear to be bursting at the seams. Although these changes may not be obvious to someone looking at the system afresh, we hope that it will lead to better, more productive and less stressful work going forward.

[Now, a brief aside for the flora of Las Campanas Observatory]

This was a very special trip for me because I thought that, when leaving the mountain in March 2023, that I wouldn’t return to LCO after graduating. Amid the satisfaction of good progress in the work here, I have equally enjoyed seeing the mountain with new eyes. Since my last time here, I’ve learned quite a lot about native Sonoran desert plants and was very interested to see similarities with the flora of LCO. The plants here cope with even harsher conditions than Tucson, and the mountain in general is very overgrazed by marauding hordes of goats. Most drought-tolerance adaptions used by Sonoran desert plant can also be seen with the plants as Las Campanas.

I’d like to highlight one LCO plant in particular that I recognized immediately from its Tucson counterparts. This is Lycium minutifolium, literally “Tiny-leaved thornbush”, that grows around the hillsides of LCO. There is a beautiful, massive specimen that grows next to the hotel rooms we usually stay at near the lodge. We have several family members of the Lycium family around in the Sonoran desert, including L. fremontii and L. berlanderi. Their fruit is related to a gogi berry (L. chinense) and is considered a “superfood” often used as a dietary supplement. The genus is in the nightshade (tomato/potato) family. They are also beloved by a huge range of birds, who eat their fruits and take shelter in their dense thickets.

The Lycium species in Tucson have several drought-tolerant characteristics including small, fleshy leaves that drop during periods of dry weather. Although the bushes seem to be covered with thorns, these are actually leafless branches that taper to points. One of the main ways to identify species in Tucson is to “shake hands” with the plant: different species have dramatically different pointy ends and leaves. Some species that grow in less stressful conditions can feel soft to the touch.

By comparison, the Lycium at LCO is a thornbush on steroids. Its leaves are an order of magnitude smaller than the Sonoran desert plants, meaning that it loses less water through transpiration. Its pointy branches can basically be considered a middle finger to the world, saying “come and try to eat me”. They are incredibly sharp and strong, even compared to the unfriendly variants that grow in Arizona. Because of this, they remain one of the only bushes that keep their leaves amid the grazing pressure from goats and donkeys. All together, the plant is a very interesting reflection of the different challenges and pressures of the Chilean desert compared to the Sonoran.

Left: L. minutifolium at LCO. Right: L. pallidium at Petrified Forest National Park

Song of the day

If you only listen to one song I ever recommend on the XWCL blog, it should be this one. It comes from my favorite album of the 2010s: “Age of Adz” by Sufjan Stevens. This song is the final track on the album, it is 25 minutes long and it is a masterpiece. Listen to it when you are driving in the car. It goes through the full range of human emotion and some day I will find a party where we can dance all the way through it. I remember listening it to the first time when I was 18, driving under the St. Johns bridge in Portland and not believing that it could change musical passages yet again. I remember listening to it while driving through eastern Maryland in Fall 2019, stuck in traffic and dancing in my seat. And now, I will remember listening to it while walking up to the cleanroom at LCO, 18 minutes deep and thinking that I need to take an extra lap so that it can finish before I get back to work. I hope you might enjoy it as well.