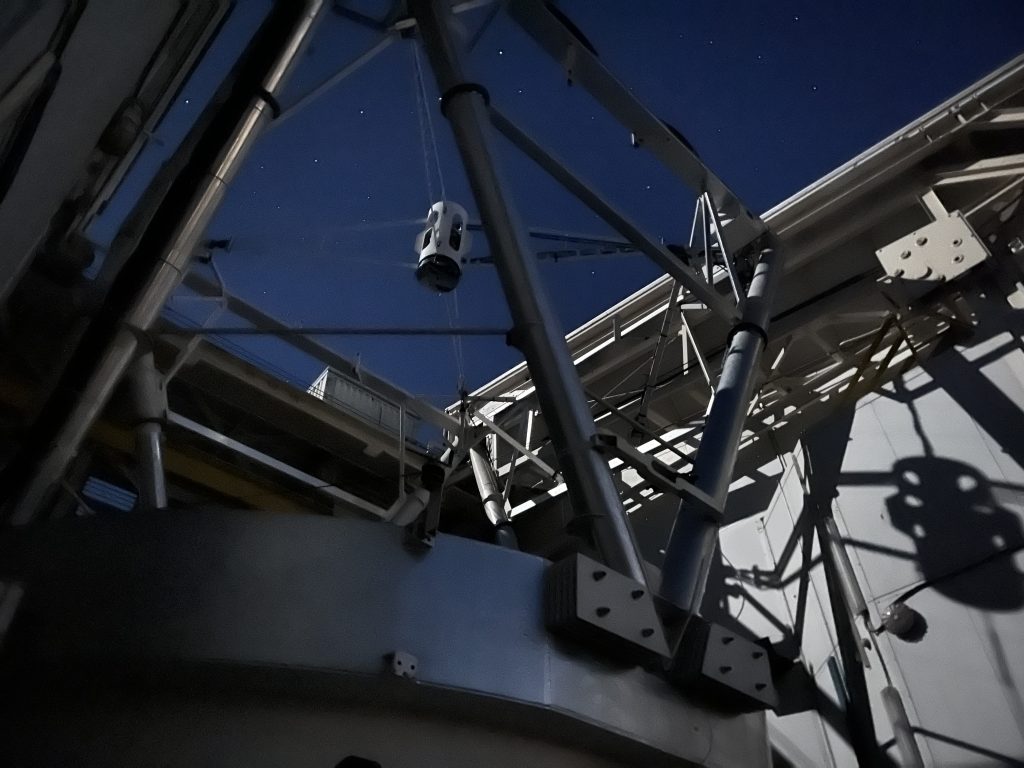

After the previous night’s untimely clouds, we were fortunate to have clear skies and moderate-to-good seeing all night. The MIRAC-5 team continued work on their instrument, which the adaptive optics operator Eden found extremely useful for its fast video feed showing how (and if) our adaptive optics experiments were improving their images.

I, however, mostly spent the night shmim-wrangling.

MAPS (like its cousins MagAO-X and SCExAO), uses shared memory images—shmims—to relay data at high speed from a wavefront sensor, through an adaptive optics loop, to the point where commands are handed off to the adaptive secondary mirror.

Of course, a shared memory image is just a hunk of memory with a hint about the type of data it contains (floating-point numbers, integers of various sizes, etc.). One could just as easily use a shmim to store a vector, or a single number, or a data cube.

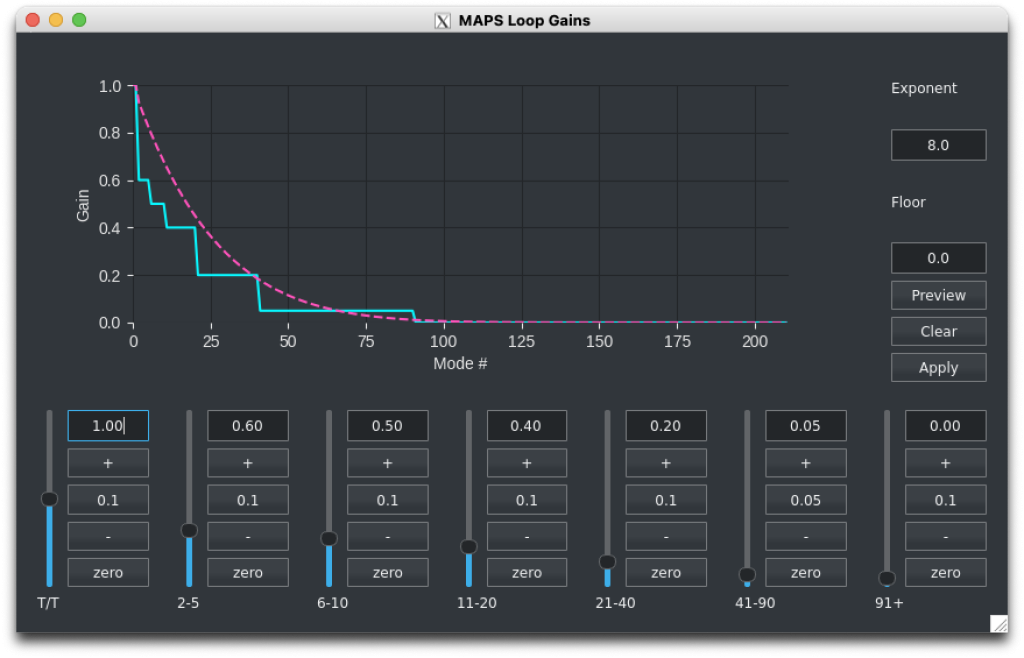

One such vector was my target yesterday: the vector of “modal gains.” Each entry in the vector scales the system’s correction for that mode by the factor you provide, allowing you to correct low-order modes more strongly while easing off the high-order modes that you may not be able to control as effectively. It’s sort of like the EQ sliders on a stereo.

Still, one may ask, what is a “mode” in an AO system? The answer: something too abstruse, dear reader, to bother this blog with.

That won’t stop me, though! You know how the optometrist fiddles around with their equipment to find the best focus for your eyes, and only then starts in with the next level: correcting for astigmatism? Well, AO systems fiddle around many times per second to get the best focus for the telescope, and the best astigmatism correction, and a few more besides. It turns out there are “levels” beyond astigmatism, accounting for even more subtle changes to the image. We need to correct those for the sharpest image possible.

That’s the short version, anyway. The long one involves math. If you’re looking for a low-stress beach read this summer, I can recommend Adaptive Optics for Astronomical Telescopes by Hardy (1998).

In MagAO-X we divide the gain controls into blocks of modes and use buttons to bump them up or down to improve our correction. MAPS does not use all the same MagAO-X software, and the two of us from the MagAO-X team were missing the fun of clicking a lot of buttons really fast. So, while Andrew develops the real, production-grade, network-enabled button-pushing infrastructure for MAPS, I brought a little bit of MagAO-X from home.

This tool replicates the UI we have for MagAO-X gain tuning, with the additional trick of a parametric gain curve. Rather than tuning the modes by blocks, one can type in some parameters to define that pink curve with a different gain value for every single mode. Clicking “Apply” then fires the numbers off into the appropriate shmim, where they are applied to the AO loop.

Of course, all the software in the world can’t change the laws of physics. Summer seems to have finally made it to Mt. Hopkins, and with it the need for active ASM cooling has become acute. It turns out that bending glass mirrors takes a lot of power, and some of that power escapes as heat. That heat, in turn, makes the whole system (red-faced and panting) call for a time-out while it collects itself.

It’s not often I wish a mountaintop were colder and windier. Tomorrow’s our last night, and we’ll have to see if we can keep our cool when it’s a balmy 54ºF at 1 A.M.