My blog post for tonight was inspired by the coincidence of Katie searching the online astronomical database SIMBAD for a bright star near where I wanted to point on the sky and finding “AO Men.” No, Laird and Jared haven’t been honored with entries in SIMBAD. As I said, it was coincidence. Variable stars, as they are discovered, are designated by capital letters starting with R, followed by the constellation name (or abbreviation). But there are lots of variable stars (in fact, when you get into the details with Kepler, there are hardly any stable stars, but let’s not go there right now), so after R-Z, then variable stars are called with double letters RR-ZZ and then AA-RR. So, AO Men is the 69th (or something like that; there are a lot of arcane rules of the naming, see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Variable_star_designation) variable star discovered in the constellation Mensa. As I said, there are a lot of variable stars, so all the constellations I had the energy to check had an AO.

This led me to consider these stars as friends of AO:

AO Men – Unfortunately, there’s no constellation Womensa, but if we consider “men” in the sense of “humans”, Katie and Jared certainly qualify as AO Men (get it — yeomen), as they do an incredible amount of work up here to make this run a success.

Quote of the night: Jared, bragging about his hand strength — “That’s AO Men right there.”

AO Car – the little manual transmission Toyota that I drive up to the dome in when I’m too tired to hike it.

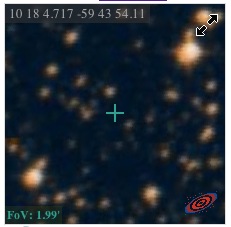

(Note: the coordinates are not exact for the named stars in the little Aladin-Lite images because of how I did the screen shots. If you want to observe these AO stars, look up your own coordinates first!)

(Note: the coordinates are not exact for the named stars in the little Aladin-Lite images because of how I did the screen shots. If you want to observe these AO stars, look up your own coordinates first!)

AO Cap – the hard hats the team has to wear when working in the dome (modeled here by me in a selfie)

AO Pup – The vizcacha, of course. Sadly, I haven’t seen her on this run yet.

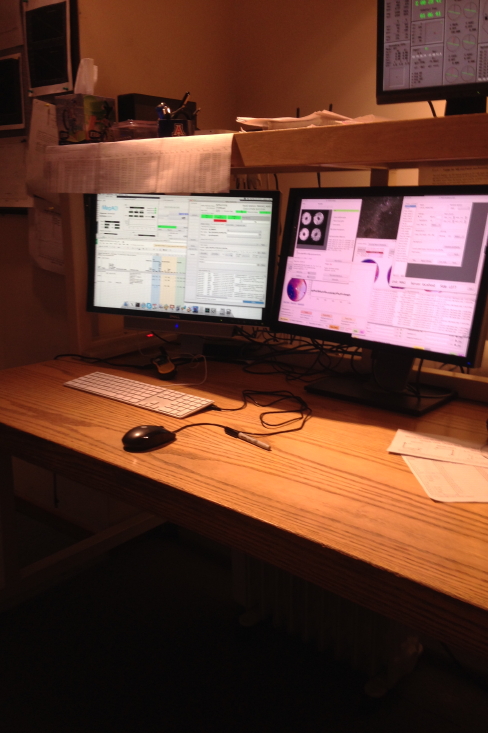

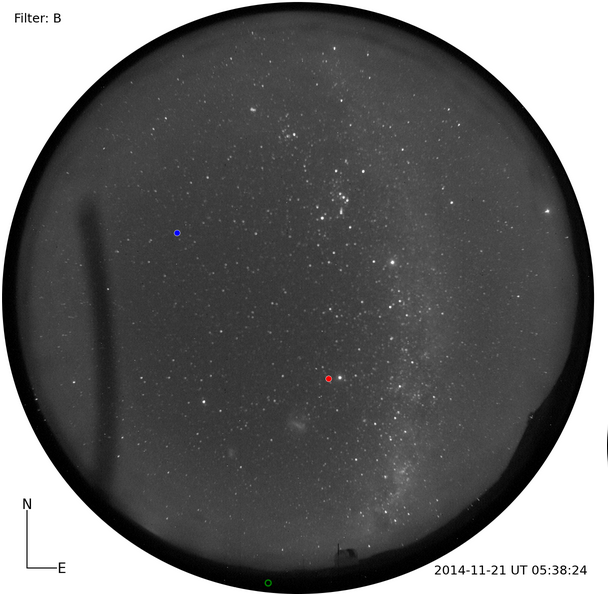

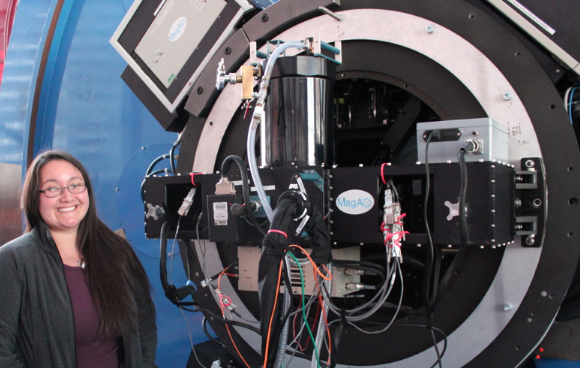

AO Cam – The wavefront sensor detector. The system has been running so smoothly that it’s been largely ignored. See — no one is in front of the AO Cam in this picture from tonight. In fact, as I was writing this, the screen saver on the computer went on.

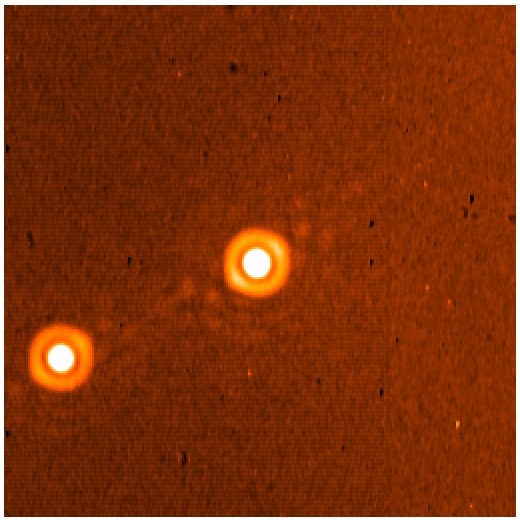

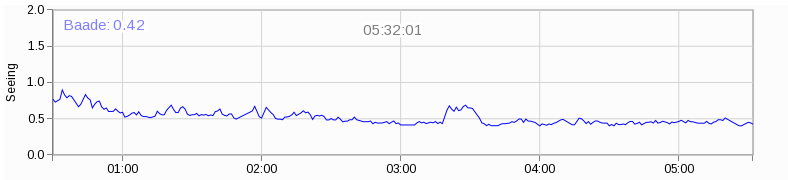

And finally, the star as my favorite question, “What is ‘AO For‘?” Tonight, the answer is that it’s for producing awesome images of young stars so I can image their disks and planets (if they have any). Of course, the night wouldn’t be complete without a binary star (it’s not AO For, but it’s what AO is for):

Here’s one thing that doesn’t vary: MagAO is awesome.

Katie is insisting there be a song. I chose this for the lyric, “After changes upon changes

We are more or less the same.” And because I just really like Paul Simon.