We had an all-Laird, all-Hα night. With everything working so well, the most exciting thing going on instrument-wise was the initial setup, which I was able to get in on.

From our control workstation, I dutifully applied the “F-test” (which displays the letter “R”, for reasons lost to history), applied the “J-test” (works as advertised), performed the 253-click process to satisfy the prerequisites for the automated alignment loop, and then performed the other remaining steps when the automated alignment loop ran away. (“Apparently it’s shy and only works when it’s just me and the instrument” — Jared)

Then, we went to look at a star, and instead found two!

Visible near α Eri at almost 12 o’clock, the companion (star, not planet) lies at about 0.25″ separation. Without an adaptive optics system and a decent-sized telescope, you’d have a hard time seeing it at all. With the AO correction, we get diffraction rings around the stars in the scene. That means we can’t get any sharper—or resolve any more details—without a bigger telescope.

Speaking of binaries, we also imaged Mira (ο Ceti), a red giant star with a companion star.

Hmm, one star has a nice core and diffraction ring, but Mira (in the center) does not look as sharp. Why does the scene look so different from the first binary? Baby, don’t you go over-analyze. No need to theorize; I can put your doubts to rest.

Mira is 400x size of the sun but approximately the same mass. So, a big puffball. But the reason for the fuzzy image is not (just) that the star is a puffball. It has to be a nearby puffball for our system to resolve it. We can actually measure half a dozen pixels across the star, though our choice of filter and telescope means that’s only two “resolution elements”. (That’s just physics saying you can use as many pixels as you like but you ain’t getting any more information.)

I regret to inform you that on this night, there were no viscacha observations recorded. But worry not, gentle reader: many graduate students have gone on to have perfectly good careers using only archival viscacha data.

So, instead, I’ll share some computer stuff.

(Yeah, I know, I know. Just shut your eyes and scroll really fast to get to the song.)

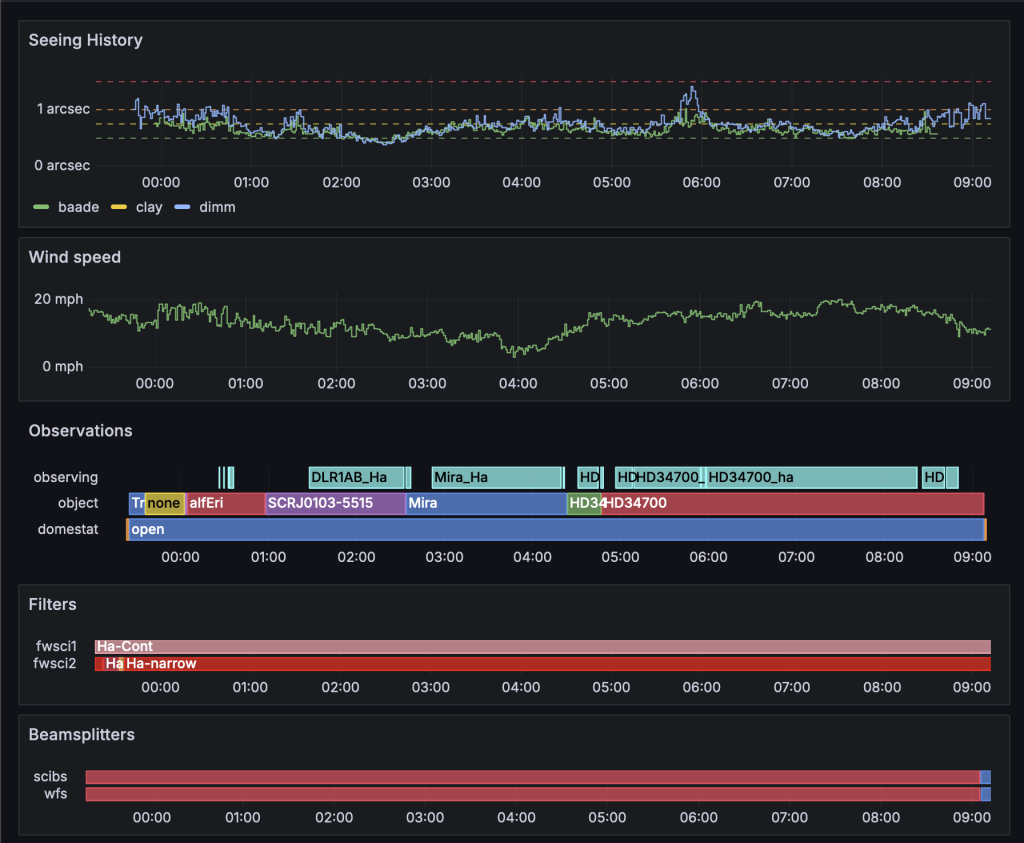

It’s not entirely new this run, but I’ve been doing some shaking-out of the data pipeline feeding our dashboards (among other things). This is what a “normal” night looks like: most of the time we’re open, we’re saving data (that’s the “observing” row on the Observations chart). Since it’s a Laird night, it’s all Hα imaging, and everything’s colored red for our filters and beamsplitters.

Before an astronomer takes exception to me calling this a “normal” night when the seeing was hovering around 0.75 arcseconds, I should clarify that ≤0.5″ nights are the only ones worth seeing, the only place worth being.

Song of the Day

Bonus Literary Interlude

—No multipliques los misterios —le dijo—. Estos deben ser simples.

“Abenjacán el Bojarí, muerto en su laberinto” by Jorge Luis Borges (1949)

Recuerda la carta robada de Poe, recuerda el cuarto cerrado de Zangwill.

—O complejos —replicó Dunraven—.

Recuerda el universo.

In English:

“Don’t go on multiplying the mysteries,” he said. “They

“Ibn Hakkan al-Bokhari, Dead in His Labyrinth” by Jorge Luis Borges (1949)

should be kept simple. Bear in mind Poe’s purloined letter,

bear in mind Zangwill’s locked room.”

“Or made complex,” replied Dunraven. “Bear in mind

the universe.”